When Chris sits in his Narcotics Anonymous meetings, he’s often the only Black person in the room. He said when he tries to raise issues related to being Black, it makes people “uncomfortable.”

Chris, who asked not to use his real name so he could be frank in discussing his recovery and work in substance abuse harm reduction, is 60 and a military veteran. He’s been sober for more than 18 years, but he is still standing on the razor’s edge of addressing racism while also relying on his peers for recovery. He feels forced to “speak white.” Even using that process, which experts call “code-switching,” discussing racial disparities is a problem.

“You’re never going to get to say anything about the disparity” because some white participants push back at discussing racism, he said of the impact of having to make his language and behavior fit into a mostly white space.

A huge disparity does exist in relation to opioid overdose deaths, said Ingham County Health Officer Adenike Shoyinka. She noted that the county has a robust opioid prevention program —with prevention services and medically assisted treatment — but “we still see that disparity where Black and brown people” have “rates of overuse death that is almost twice the number of people who are white.”

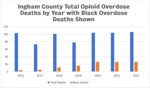

Ingham County’s Black population is 12.6%, but 25% of opioid-related deaths in the last three years have been Black residents, according to Ingham County Health Department overdose rates. Overdose deaths in the Black community in 2016 were 3% of the total overdose deaths.

Similar racial disparities arose during the COVID-19 pandemic. “In 2020, Black Michiganders saw COVID-19 death rates of 22.8 per 10,000 people, significantly above the national death rate of 15 per 10,000 in 2020,” a report on the epidemic from the state’s COVID-19 Task Force, led by Lt. Gov. Garlin Gilchrist, said.

But the task force, working with medical professionals and public health, was able to reduce that disparity. “The Task Force’s work paid off, with COVID-19 death rates for Black Michiganders dropping to 16.2 per 10,000 in 2021 and 8.6 per 10,000 in 2022. Nationwide, Black Americans’ COVID-19 death rates dropped from 15 per 10,000 in 2020 to 14.8 per 10,000 in 2021 and 6.1 per 10,000 in 2022.”

Shoyinka said the concentrated work in addressing COVID disparities was something the county and others would have to tackle in addressing the growing racial divide in opioid overdoses.

“Public health still has a lot of work to do to dismantle the structures in place that get in the way of us closing those gaps,” Shoyinka said.

The county, she said, has improved over the last decade in identifying and addressing racial disparities. Much of that has relied on meeting people “where they live” and addressing the social determinants of health. That’s a complicated public health frame that addresses a variety of issues related to where a person lives, which may be contaminated with lead or other toxins, to what they are eating, and how they are socializing.

“It is complex,” Shoyinka said.

Chris’ professional life is working in harm reduction, he often finds himself in majority white spaces. There, the focus is on accumulating data, but not necessarily asking what the data reveals and why there is a disparity. He said that he feels like he is creating statistics about “lynching” without asking why the lynchings are happening in the first place.

As a result, he sees the disparity being lost.

“It’s a body count,” he said.

Raising that concern, he said, is met with stiff resistance. Raising that issue in the professional, sterile, state-data-collection operations faces pushback.

He recalled in the Army being told he was “one of the good niggers” when he was stationed in Texas. In his experience, the attitude in state offices looking at overdose and use statistics is the same.

“Any Black man talking like that in the office is going to find himself feeling quite alienated,” he said.

Over on Lansing’s east side, operating out of a room in the Fledge, is Punks With Lunch. The 6-year-old nonprofit runs a syringe exchange and distributes Narcan, a drug that stops an opioid overdose, as part of its harm reduction efforts. It’s funded by a grant from the Michigan Department of Health and Human Services.

Julia Miller, co-founder of the organization, said about 15% of the people who use its programs are members of communities of color, based on rough data. She finds that she is engaging and supporting more people of color during the group’s street outreach work, rather than through her office in the Fledge, “where it’s easier to develop a strong relationship.”

Shoyinka said that the county is working on addressing disparities, but “there’s more work to be done.”

“One by one, we have to make sure that we address the unique populations that are significantly affected,” she said, “and so we need to prioritize that and include that in our strategies.”

Support City Pulse - Donate Today!

Comments

No comments on this item Please log in to comment by clicking here